Article written by intern Miguel Loustalot

From October 28 to November 2, the world witnessed COP16 – the 16th Conference of Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. Delegations from over 200 countries gathered in Cali, Colombia to determine the implementation of the global framework for biodiversity following its adoption in Montreal two years ago. This framework dictates 23 goals that the world must achieve by 2030, including the protection of at least 30% of the planet’s surface, and the restoration of at least 30% of all damaged ecosystems.

The COP16 summit concluded with some historic achievements but also many disappointments. The role of indigenous peoples and people of African descent as key stakeholders in nature conservation became recognized in international climate policy for the first time in history. The official delegations at the summit also established the Cali Fund, which allocates a portion of the profits generated by laboratories and companies utilizing species’ genetic information to support environmental protection.

However, global negotiations concerning the crucial aspects of the summit were abruptly halted a day later than planned. No consensus was reached on the financial and tracking strategies proposed in the previous Montreal Agreement.

Despite the diplomatic setbacks, local communities, particularly women activists, demonstrated that meaningful environmental protection efforts originate at the grassroots level, where mobilization and local initiatives catalyze change. Praktik Solidaritet’s partner organization Corporación para el Desarrollo Regional (CDR) – which is also based in Cali – mobilized ahead of the COP16 summit through a series of dialogue meetings with women climate activists and feminist networks from across Colombia and other Latin American countries.

”We are a key part of biodiversity!” exclaimed participants at one panel discussion. According to the UN, women are most vulnerable in the climate crisis because they tend to be in charge of producing food for their families and communities; mostly in the Global South. Women also often possess extensive knowledge about agriculture and the preservation of their natural environment.

Ironically enough, women usually have fewer material and social resources compared to men. CDR named the conferences that took place at Cali’s most important university encuentros de mujeres populares y cuidadoras del cuerpo, territorio y hábitat (dialogue meetings for women activists and defenders of body, territory, and habitat) to emphasize women’s importance surrounding the protection of the environment, their local community, and their family. During these encuentros, women activists were able to share their views and experiences from a personal and a feminist perspective.

Biodiversity intersecting closely with Human Rights

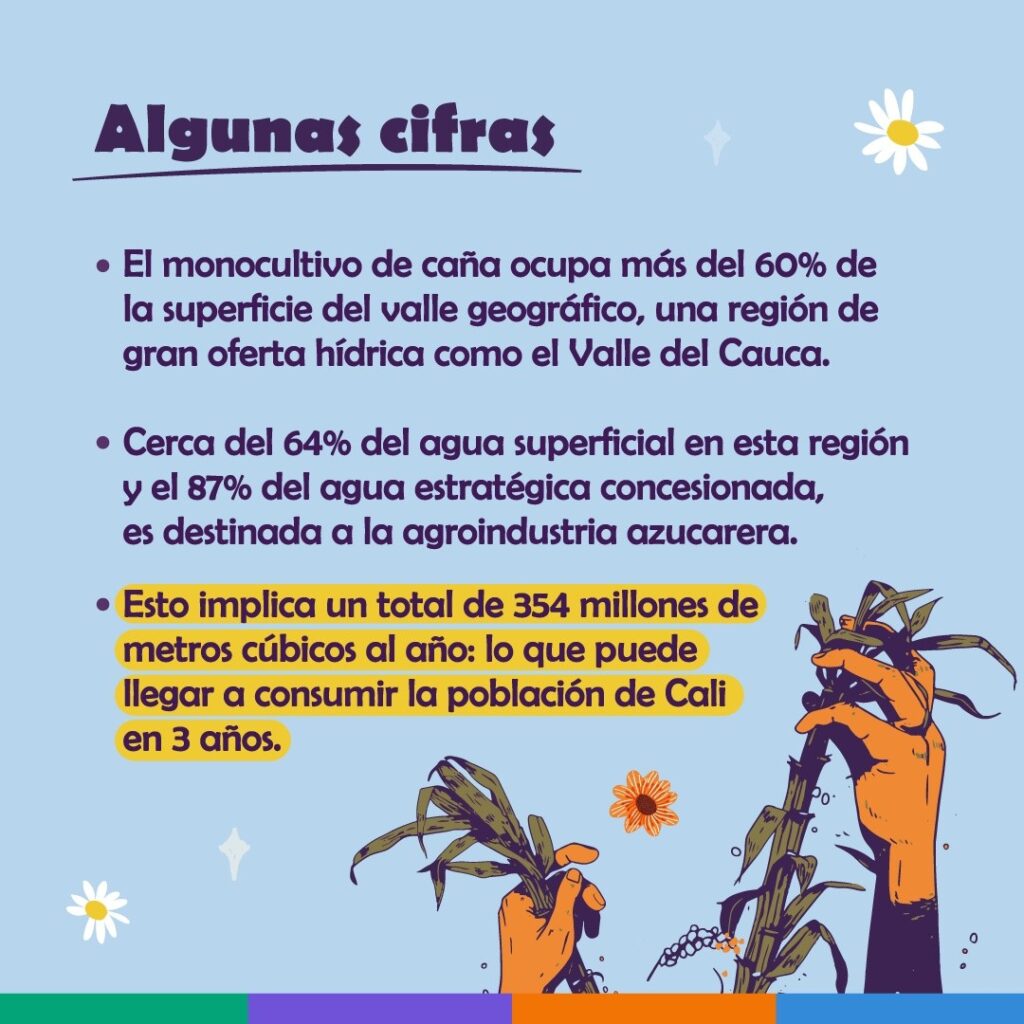

Activists from Cali highlighted at the conferences the most concerning environmental issue afflicting the region: monocultures of sugarcane. A monoculture, deriving from the ancient Greek ’mono’ meaning ’one’ and the Latin term ’culture,’ involves the practice of growing a single crop at a time, contradicting nature’s preference to work in complexity.

”The problem is not the crop of sugarcane itself, but the ways it’s cultivated,” asserts Cali-based environmental researcher and educator Dr. Daiana Campo. ”When you prioritize a single species everything in nature must be transformed to ensure that species’ dominance. If there’s other vegetation, it must be removed. If you remove vegetation, you break an entire ecosystem cycle; a food network.” CDR, along with women activists and environmental organizations, are fighting against the proliferation of sugarcane monocultures in Cali’s region, Valle del Cauca, primarily because they prevent local farmers from producing their own food, not to mention their negative effects on the surrounding soil, water, and biodiversity.

Dr. Campo explains that the impact of pesticides in monocultures is so profound that it renders the soil unusable after several growing seasons. The mass cultivation of sugarcane also requires enormous quantities of water, leading to the depletion of nearby lakes and swamps, and forcing local communities to find new areas for agriculture. ”The cultivation of monocultures is a practice specifically structured to prioritize a broad expansion of a particular species. Such expansion is not only technical, but also economic and political. I conducted research on the area of Candelaria, and I can tell you: out of 29,600 hectares, 26,500 were spared exclusively for sugarcane.”

Local environmental activists recognize as much as international law the access to food and water as a fundamental human right – a recognition that resonates deeply with the Latin American concept of una vida digna (a dignified life). CDR’s conferences emphasized that this struggle for dignified life must include fair distribution of natural resources and recognition of women’s role as environmental defenders and decision-makers within climate policy. Dr. Campo expanded on the concept: ”Enjoying a dignified life doesn’t just involve my wellbeing but rather ensuring that my neighbor is living good as well. That it is possible for that closeness, that proximity that I have built with others, not to weaken.”

While official negotiations at the UN biodiversity summit may have fallen short of expectations, COP16 served as a reminder that meaningful environmental progress flourishes through grassroots initiatives rather than diplomatic venues. CDR’s encuentros de mujeres united more than 500 women activists in a powerful compilation of dialogue and action, fostering tangible steps toward environmental justice and sustainability culminating with an agreement of mutual cooperation. As noted by Dr. Campo: ”Environmental protection is an action of the highest responsibility, which cannot be delegated to just anyone, and for which each of us should assume our part.”

This article was written and the interview with Dr Campo made in December 2024.

Here you can watch videos and photos to know more about the dialogue meetings and CDR events around the COP16 – and much more their activities!